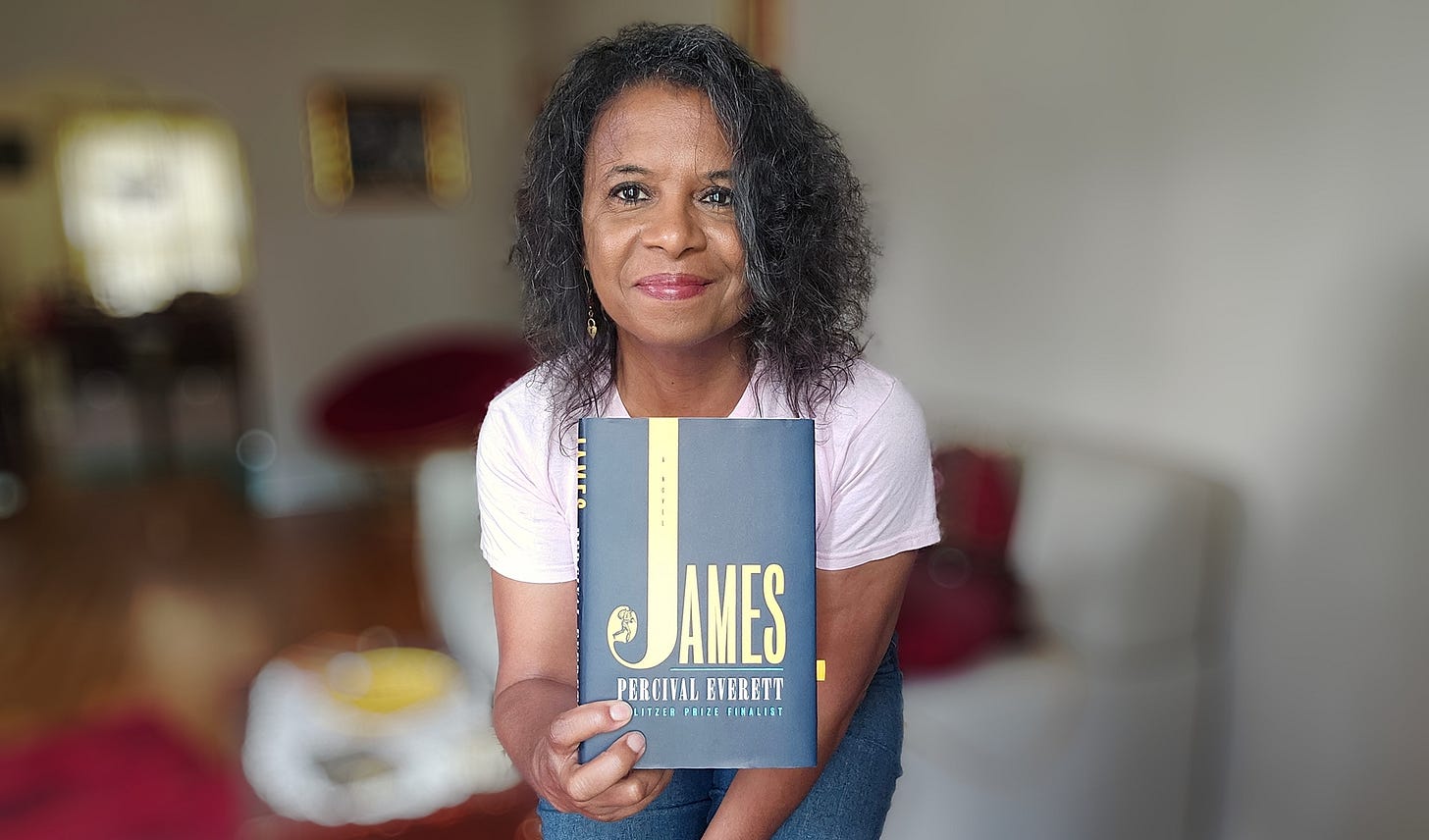

In real life, I fall in love with the wrong men. But in my literary life, I always fall for the right ones. Recently, I fell in love with Percival Everett. I mean, his brain. Or more specifically, his writing. And even more specifically, his new book, James.

In James, we get Jim’s story, not as Huck saw him in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but in Jim’s—James’—own voice.

James has been called a “reimagining,” a “retelling,” or a “reworking” of Mark Twain’s classic. But Everett feels those words miss the mark.

“I consider myself in conversation with Twain,” Everett said in an interview with Jeffrey Brown of PBS News Hour’s Canvas. “I'm perhaps writing the novel that he was not equipped to write, and nor would he even imagine it, because his character is Huck Finn. It's Huck's novel. But he could not occupy the psychic and cultural space that was occupied by Jim.”

Or, as Everett put it in an interview with Walter Isaacson, “It was his [Twain’s] business to tell the story of the white youth and it is my business to tell the story of the Black man.”

And boy does he.

Percival Everett is the author of more than 30 books, including Erasure, on which the Oscar-winning movie, American Fiction, is based. He is also a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and a Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Southern California.

James is truly the Adventures of James. The beginning provides a glimpse of James’ family life, the respect and love everyone has for each other; James’ intelligence and his hidden love of books and knowledge; and his relationship with Huck and others that are enslaved.

But by page 35, after James learns he’s about the be sold, he runs away, both to save himself from being separated from his family and to buy himself time to think about how to get them all to freedom. Huck, who has staged his own death, joins him.

Then, the adventure, filled with tragedy and comedy, begins.

Why am I laughing?

Correspondent Martha Teichner, in an interview with Everett for CBS News Sunday Morning, stated, “Everett's books are often perversely funny. Imagine a funny novel about lynching (‘The Trees,’ from 2021), written in the form of a police procedural. Funny, until it isn't.”

I haven’t read The Trees (nor do I remember reading Adventures of Huckleberry Finn), but that’s how I felt about James. I’m awed by Everett’s skill at making something tragic, funny.

Take, for example this scene.

After James finishes teaching his children how to translate their correct English into incorrect English, he later combines that lesson with what he calls “situational translations.” Beginning with the hypothetical situation of Mrs. Holiday’s kitchen being on fire without her being aware, he asks his children how they should tell her, translated into a way she, as a white person, will want to hear it coming from someone Black.

“Fire, Fire,” January said.

“Direct. And that’s almost correct,” I said.

The youngest of them said, “Lawdy, missum! Looky dere.”

“Perfect,” I said. “Why is that correct?”

Lizzie raised her hand. “Because we must let the whites be the one to name the trouble.”

“And why is that?” I asked.

February said, “Because they need to know everything before us. Because they need to name everything.”

The lesson continues. James then asks them how they should tell Mrs. Holiday to put out the fire.

Rachel said, “Missums, that water gone make it wurs.”

“Of course, that’s true, but what’s the problem with that?”

Virgil said, “You’re telling her she’s doing the wrong thing.”

I nodded. “So what should you say?”

Lizzie looked at the ceiling and spoke while thinking it through. “Would you like for me to get some sand?”

“Correct approach, but you didn’t translate it.”

She nodded. “Oh, Lawd, missums, ma’am, you wan for me to gets some sand?”

The ridiculousness of him teaching his children how to speak incorrect English and appear stupid, along with the way Everett portrays the lesson, is funny. But it is also sad and the underlying reason for it is sobering. If his children don’t learn these lessons, if they ever slip up for even a moment, if they are ever seen for who they really are, the risk of them being whipped, lynched, or sold is very real.

This is James’ reality, something he deals with on nearly every page. And, like many others, it’s a reality that spills beyond the pages of James, to the reality experienced by Black people from the time of slavery into the Jim Crow era and beyond, even today. One example: While it’s not exactly the same, James’ lessons made me think of how Black parents teach Black boys (and girls) to interact with the police today.

When Brown asked Everett to discuss his mix of humor and horror, Everett said, “If you get someone laughing, then you have removed some defenses. You have removed some walls. And then you can show them the bad things. To have someone ask themselves why they're laughing, then you have done something even better. I don't go to work with a message or a mission, but I do hope to generate thought.”

Everett succeeded. As frequent unexpected barks of laughter escaped my lips, I asked myself, why am I laughing?

The adventures of Jim

James is a page-turner. With James’ every action, the danger grows—and so does his exhaustion.

After he and Huck have lost their boat and just stolen a skiff belonging to robbers, Huck is prattling on about genies and lamps while Jim is rattled by what just happened and concerned for his safety. He repeatedly responds to Huck’s trivial questions, before thinking to himself, “Entertaining such discussions in character was exhausting ...”

His discussion with Huck is just one example of his exhaustion. We are painfully—and comically—aware of what being forever in character is like for James, a man who reads Rousseau and Voltaire, who is writing his life story in a stolen notebook with a stolen pencil, and whose only outlet for philosophical debates about racism and slavery are with Voltaire and John Locke in his dreams. He is a man who must be ever vigilant to “always give white folks what they want.” He is a man who must never be really seen.

But, of course, even that is not enough to keep him safe. As James says to his friend Norman, after Norman asks him what he did to get whipped:

“What did I do? I’m a slave, Norman. I inhaled when I should have exhaled. What did I do?”

The danger forever looming over James’ head throughout his adventures made me breathlessly turn the pages to see what would happen to James just because he “exhaled.”

The brilliance of the writing

When I first stumbled upon the audiobook of James, I fell in love with the story, brought to vivid life by actor Dominic Hoffman. When I bought the book to review for this column, I fell deeper in love with the genius of the storytelling by Everett. I loved the double-meaning of nearly everything James says.

Like when he tells Huck, “I can keep me a secret, Huck. I kin keep yo secret, too.”

His answer is much more than a reassurance to Huck. It’s a statement about his life. James is all about him keeping secrets—about who he is, about what he thinks. His answer to Huck is but one example that underneath the obvious answers James gives when questioned, lies his real answers, as close to the truth as he dares to admit.

There’s a reason why the word “James” is huge on the cover of the book. Because this is James’ book, his story, and through it, the man who is finally seen.

Thank you for reading! If you like what you just read, please subscribe—and please leave a comment. I’d love to hear your thoughts about James or your thoughts about anything else in this column.

I’m a proud member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative, a group of more than 50 talented writers, covering a myriad of topics. Check out their columns below. Also check out Black Iowa News and Iowa Capital Dispatch, two great publications that sometimes carry our stories.

Not only do you always teach me new things, you always teach me to think anew...

I just finished James and fully agree; it'll definitely be a 2025-best-book contender. I was similarly floored by how Everett weaves humor and horror together. Feel like it ought to be required reading as a former high school teacher.

Anyways, I look forward to reading more of your book reviews!